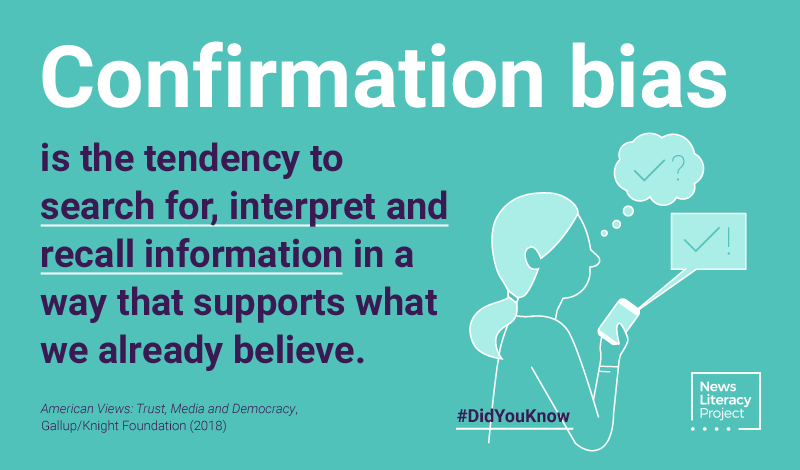

Confirmation bias is the natural tendency we have to search for, focus on, and accept information that agrees with, supports, or reinforces what we already believe. It also makes us more prone to ignoring facts that go against our beliefs, despite any contradicting evidence.

For example, a coffee lover will be more inclined to believe and share an article touting the health benefits of drinking coffee, while ignoring or disbelieving an equally credible article about the potential health consequences.

The best ways to counteract confirmation bias during source evaluation and general research are to actively seek out opposing viewpoints and find evidence that may disprove your point of view or argument.

There are several other kinds of cognitive biases, or patterns of thinking that tend to lead to inaccurate or unreasonable conclusions (Psychology Today), that can contribute to the spread of misinformation, disinformation, and conspiracy theories online, such as:

While our own inherent biases influence what we see and interact with on the internet, algorithms also play a significant role. Google and social media websites like Facebook have algorithms in place to curate personalized search results and news streams for their users based on their individual browsing history and activity. Facebook may hide the posts of your friends or family who have different viewpoints from you, or Google may push certain results when you search for something because its algorithm believes you will agree with them.

This leads to "filter bubbles," a term coined by Eli Pariser, a type of online echo chamber where we become intellectually isolated because information that may disagree with our viewpoints is hidden from us, and we are relegated into our own cultural or ideological bubbles.

Misinformation and disinformation can easily spread among these "bubbles" without anyone realizing the information they are receiving is false because so many of these spaces are fueled by confirmation bias. Such circumstances can explain why some people fall down the rabbit hole and begin sharing posts supporting conspiracy theories or fringe political movements, like QAnon.